For years I’ve been irritated over the right wing’s hijacking of the American flag. I do understand that for many, particularly veterans, the flag is sacred, but for far too many I’ve felt that flag worshiping has been more of a case of “methinks thou doth protest too much.” Flags waving from car antennas, flags on clothes and ball caps, flags on golf bags, etc. The ultimate, of course, was Trump theatrically hugging the flag at his rallies. It seemed as if these people were proclaiming that they were more patriotic than the rest of us.

|

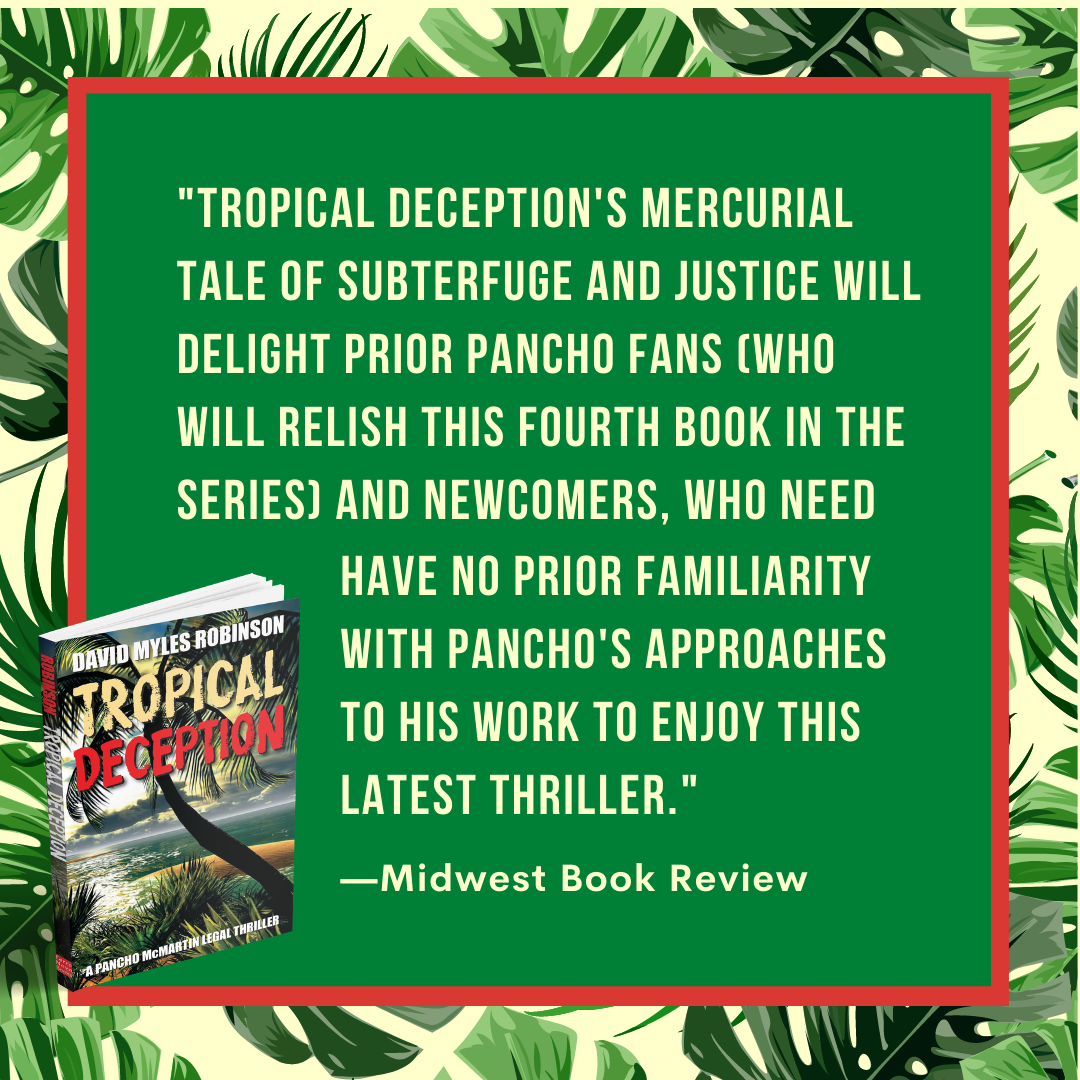

| David Myles Robinson participated in a virtual book tour for his new novel, Tropical Deception. The book tour consisted of ten posts/reviews of Tropical Deception on either social media, or blogs. Reviewers were from all across the world, including Germany, India, and the Philippines. Just under 9,000 people were exposed to the book during the tour! Take a look at each post on the tour by clicking the links below: |

In addition to human interest stories and local politics, I investigated all sorts of systemic racism. I did a story on why a supermarket chain charged more for groceries at its market in a high minority population store than at its stores in the upmarket parts of Pasadena. I quoted the smug store manager claiming that the policy was based on the fact that the minority population stole more and therefore the prices needed to be higher to make up for the losses. And I referenced a national study which showed that there was no discernible differences between shoplifting statistics in minority versus upscale white neighborhoods. The supermarket chain subsequently changed its pricing policy, which I believed was actually based on the fact that the minority community was in essence a captive market. Most people of color would not feel comfortable shopping outside of their community.

I also did a story on the lack of minority employees at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which was based in Pasadena. JPL was a big local employer, yet its workforce was nowhere close to demographic ratios. My exposé resulted in JPL changing its hiring policies.

So, despite a prior decade of civil unrest, recent riots, and the emergence of the Black Panthers, which vowed to challenge police brutality against Blacks, I lived with an overarching sense of hopefulness that things would improve. Although I was young and probably naive, I did not believe we could eradicate racism anytime soon—if ever. But I did believe that we could expose its ignorance and absurdity to such a degree that all but the most virulent racists would, at the very least, pretend they too abhorred racism and discrimination of any kind.

I moved on to law school and then to the practice of law in Honolulu, a true melting pot, where, except for the very occasional asshole haole (Caucasian) client complaining about being discriminated against by the largely Asian population, it was generally easy to de-prioritize racism as a social issue. With fits and starts (Greensboro massacre, Rodney King riots, etc.), America seemed, on the surface, to inch forward. I cried like a baby when Barack Hussein Obama was elected the 44th President of the United States.

Then America elected a man who called for the death penalty of five Black men known as the Central Park Five, even after DNA evidence proved their innocence. A man who believed that Obama was born in Africa and was therefore not eligible to be president. A man who called Mexicans rapists. A man who called white supremacists “very fine people.”

And so we come to the now. As I write this, America is in its third day of protests over the police murder of George Floyd, the Minneapolis man who died after a police officer, sworn to protect and serve, kneeled on the neck of the already handcuffed Floyd for almost nine minutes. Many of the protests have turned into riots, resulting in fires and looting. Outside extremist groups, some white supremacists, some loosely aligned left wing anarchists, have allegedly inserted themselves into the mix, although there is still much confusion about that. Propagandists are hard at work massaging the message away from the pandemic of police murders of people of color. Just as his brother fears, George Floyd is on his way to becoming a name on a t-shirt.

All of this is set against the backdrop of a viral pandemic which has put tens of millions of people, many of whom were people of color, out of work and which took but a matter or weeks to highlight the fact that millions of people live paycheck to paycheck and could not afford to buy food or pay rent.

I am an older, well-off, privileged white man, so feel free to take my perspective on all this with a grain of salt. I speak for no one but myself, but I feel compelled to speak. For me, putting thoughts to paper is cathartic. Even if only a handful of people read what I write, the process helps to release my own anger and angst.

I feel a sense of helplessness and hopelessness I cannot remember feeling about America. We have a president who provokes instead of consoles. We have 24/7 right wing news outlets which are more focused on a burning building than the death of Black people at the hands of the police; on the fact that some people are looting than on the anger and impoverishment of the looters. During and after race riots over the years I always heard variations on the refrain that ‘these people are just hurting their cause,’ or ‘they’re making their race look bad.’ Do you really think for one moment that the people who turn violent or to thievery give one iota of shit about what people think about them? About whether they are doing damage to their race? With exceptions, these people have been abused by the system their entire lives. They are strangers in a strange land. They have no jobs, or if they do, they have jobs which don’t pay a livable wage. They do not have money for food. They live in fear of gangs or the police or both. They have little hope and many don’t expect to grow to a ripe old age. The anger boils over and they react. The temptation to take stuff for free is there and they react. In the immortal words of Donald J. Trump, “what do they have to lose?”

I certainly do not condone violence, despite the fact that it is more often than not the violence which promotes reaction and change. Even in the case of Martin Luther King, it was the violence against King and the demonstrators which finally captured the attention of Americans and their politicians (think vicious dogs attacking demonstrators, or young Black men and women bleeding from their heads after being beaten by police batons). After the large riots which rocked America in the decades leading up to this century, it was the reaction to the burning of cities which got the attention of politicians and which resulted in at least lip service to change.

Perhaps the current situation will peter out and the cities filled with the hopeless and helpless and angry and despairing people of color will return to the normalcy of inequality. Perhaps the protestors venturing out in the middle of a viral pandemic will infect entire cities. Perhaps none of the above. Perhaps a leader like Barack Obama will rise from the ashes and show us the way.

I fear, however, that we are sitting on a tinder box, the fuse to which has already been lit.

In addition to Pancho, the recurring characters in the Tropical series are Drew Tulafono, a big Samoan ex-NFL player who is Pancho’s best friend, surfing buddy, and private investigator; Susan, his long-time secretary and sometime mother figure; Elise, his new, young secretary being primed to take over for Susan; and several love interests, the latest of whom is Padma, the former medical examiner for the City & County of Honolulu.

In TROPICAL DOUBTS, Pancho is asked by an old family friend to represent him in a medical malpractice case arising out of what should have been a simple surgery on the friend’s wife, but which resulted in her falling into a permanent vegetative state. Pancho is hesitant to take on the case as he is not a med mal specialist, but his friend insists. So Pancho and Drew begin the discovery process to try to determine what went wrong. But things take a nasty turn when Pancho’s friend is arrested for the murder of one of the doctors who had operated on his wife. Suddenly Pancho is knee deep in a murder case as well as the medical malpractice case in which the plaintiff is an accused murderer.

I don’t really think of my legal novels as mysteries, although there are certainly elements of suspense and surprise in each. It is the processof the law which has always interested me most, and which is what I enjoy most in legal thrillers I read. When I was practicing law, I loved cross-examination of witnesses, which differs from direct examination in that it is less controlled, more exciting. Direct examination of a client or witness is well rehearsed and, if all goes well, predictable. But cross-examination is where a trial attorney can alter the course of a trial. Perhaps the examination will be subtle and polite, lulling the witness into making damaging admissions without even being aware it was happening. Or, more fun but also riskier, the cross-examining attorney may go after a witness with a vengeance. I say riskier because I will always remember one of my first jury trials in which my client was suing a homeowner for negligence. The homeowner was a fireman, who had lied during his deposition and I went after him hard, forcing him to admit over and over that he had lied. I lost the case and, in talking with the jury afterward, it became clear that I’d been too hard on the fireman during my cross-examination. Juries tend to have a great deal of sympathy for firemen and policemen, and even if they are caught in lies to protect themselves, the juries will give a close call to the first responder. A lesson learned.

I have to resist the temptation to lean on the drama of a great cross-examination in my novels as the key to Pancho winning his case. The first Pancho novel, TROPICAL LIES, did just that, and most readers responded well to the courtroom scenes. But I quickly learned that novels written as series (albeit stand-alone as a story) stand the risk of becoming too formulaic and predictable. I hope that each of my Tropical novels so far is different enough to entertain and, when appropriate, surprise. I don’t know what’s in store for Pancho next, but I do have some ideas floating around. I like to take a break from the legal series after each one and write something completely different. I’m hoping that by doing so I will keep things fresh and new.

They came to escape violence

They came from extreme poverty

Seeking a better life

For their children

Now jailed

As hostages

In a game of hate

Go home and die.

It went down hard

And lumpy

Like coal

But he got the job

And now all he has to do

Is kiss a lot of ass

Tell a lot of lies

And bear witness to the last of an empire

Politicians

Goose-stepping away the last of their dignity

And integrity

Bidding a fond adieu to democracy

Which was pretty much shit anyway

Look what it gave us

Wannabe a strongman?

Wannabe an autocrat?

Wanna get rid of the people of color?

And the free press?

And dissent?

And morality?

Now that democracy has failed

What grand experiment shall we try next?

| Published May 1, 2018 Review: "Robinson’s shocking page-turner elaborately weaves historical figures and events into a mind-blowing whodunit that will leave readers on the edge of their seats. Interspersed throughout the mystery are informative details that round out the historical fiction work." - San Francisco Book Review |

THE PINOCHET PLOT is somewhat political in that it involves some interesting and disturbing times in US history, and the plot of the novel, by necessity, had to be political in order for the fictional conspiracy to make sense. It was a fun and sometimes unsettling novel to research in the way that crazy reality can sometimes overshadow even the most off-the-wall fictional scenarios. My research into the CIA sponsored drug experimentation program, MKULTRA, and then into the CIA’s involvement with the brutal Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet, disclosed such outrageous behavior that I decided to try to make the fictional part of my story even more outrageous than reality, although frankly, I’m not sure that was possible.

I also played around with various layers to the storyline in PINOCHET. There is Will’s quest for the truth about his father’s murder; the sad realization of his mother’s life of fear and anger; the horrifying discovery of a national political conspiracy; and the love story between Will and Cheryl. Interspersed throughout, I employed a device I remember Kurt Vonnegut (one of my favorite authors) sometimes using, which was for the author to step away from the story at certain moments to speak directly to the reader, generally to educate or remind the reader about real facts, such as suicide rates, welfare fraud, and our own depressing history of oppression and even genocide of our Native Americans.

What I’ve thought about, given the fact that I completed the novel well before Trump was elected, was how I would have handled some of the political diatribes by the murdered liberals had I had current events to play with. As I write this, I’m thinking about an article I read just this morning in which certain journalists are actually afraid for their lives, and the lives of their families, as they have been getting death threats and other forms of scary harassment from angry Trump supporters. One wonders how outrageous my fictional conspiracy will turn out to be.

My next novel, SON OF SAIGON, is what my agent described as a “Boomer buddy” story, as two older guys (70ish), best of friends, set out on a quest to find the son the one friend never knew he had. The story itself is fun and suspenseful, but my main goal was to highlight the reincarnation of both men’s lives with the introduction of an intriguing quest, adventure, and yes, even love.

The third novel to be published toward the end of this year is another in my Pancho McMartin legal thriller series. TROPICAL DOUBTS starts out with Pancho taking on a medical malpractice case for an old family friend. It is an area of law he doesn’t really practice, but his friend is insistent. Before long, however, Pancho finds himself embroiled in both the med mal case and a related murder case.

What got me thinking after watching those two movies was not the overt or the metaphorical social issues, but the difficulties artists in any medium have in describing love—in conveying to the reader or the theater-goer or the audio listener or the person staring at a painting, that they are experiencing a perfect example of love. Think about it. Is there a particular movie, or book, or poem, or song, or painting which, to you, exemplifies pure love?

Do plays or songs in which one or both lover die in the name of love actually convey a relationship of love? Seriously, is it really an expression of true love to kill oneself because one’s love is unrequited? Or for both to die in a love induced suicide pact? Aren’t those acts of selfishness rather than love? Although it can certainly be argued that there is always an element of selfishness in love.

In one of the movies I referred to above, the director attempted to convey the budding love between the two men by shots of them doing things together—riding bikes, lounging by a lake, reading books, or running up a mountain together, free spirits alone in the outdoors. Much of their dialog felt stiff and not real, which didn’t do much to show me these men were falling in love. The words themselves were strung together into sentences and into paragraphs which contained the author’s meaning, but without being convincing. To me, they sometimes sounded like one of Hemingway’s characters for whom English was not a first language, so that the dialog was very formalized, the way a foreigner would speak trying to be correct and proper. While that manner of speaking was brilliant for what Hemingway was trying to convey, it was silly and unbelievable as between these two speakers of English and did nothing to convince me they were in love.

One scene that drove me a little nuts was after they returned to their hotel from the mountain and burst into their room laughing uproariously. Okay, so they had obviously bonded and were having fun, but I wondered what they were laughing about, or was just the fact that the two were laughing together a sign they had fallen in love? Had they run through the lobby of the hotel and up the stairs and into their room laughing out loud over something shared sometime earlier? I mean, who does that? Sorry if I’m too picky, but all that running around smiling and laughing about something which we, the audience, know nothing of, seems too contrived and told me nothing about what it was that caused these two men to love each other (other than physical attraction).

In the other movie, the one about a love between a mute woman and a fish, the love, whatever love is, actually felt more real to me. We were shown the emotional and physical agony endured by each of the parties and we were able to feel the love grow with each gentle act of kindness and exploration of mutual pain. So, the concept of love in that situation had nothing to do with shared books, or love of the great outdoors, or music, or even any shared experience other than how each had been treated and abused by the world around them. Theirs was a kind of organic love, grown from each one’s personal demons and needs—perhaps a seed of selfishness?

My point is that love is such an elusive concept to define that it can’t help but be an even more difficult concept to portray. I have been in love with my wife, Marcia, for about 45 years now, and had only loved one other woman before that, so either I’m no expert in love because I haven’t been in love very many times, or I’m a great expert in love because I’ve only been in love twice. In either event, even as a writer I don’t feel capable of ever truly capturing a perfect portrayal of love.

I had a strange experience many years ago when Marcia and I were eating at a Peruvian restaurant in Santiago de Chile, on our way to Antarctica. Sometime during the meal, apropos of nothing, I looked at Marcia across the table and suddenly felt an overwhelming rush of euphoric love, something both emotionally and physically overpowering—so much so that I can’t even remember if I said anything. There was a warmth, and a headiness, and a sense of happiness which, to this day, makes me smile. And no, it hasn’t escaped my notice that I had to actually use the word love to help me try to describe the feeling.

In my latest novel, THE PINOCHET PLOT, there is a love story sub-plot in which the principal character, Will, knows intellectually that he loves his best friend, Cheryl, but is afraid to acknowledge it for psychological reasons related to his past. I attempt to portray the love by focusing on their easy friendship and their physical attraction for each other and, as Will begins to learn about and deal with the issues of his past, the relationship is allowed to slowly morph into an acknowledgment of love. I don’t know how well I dealt with it. I can only hope the reader gets a sense of Will and Cheryl’s bond and the mutual understanding and growth which allowed them to step beyond being friends and lovers, and become a couple in love.

I do realize that for many, if not most, people, the flowery poetry and the beautiful metaphors and similes and the Elvira Madigan moments of lovers running through a field of flowers or Dustin Hoffman in the Graduate driving up the California coast like a mad-man to try to stop the wedding of the woman he loves, will be sufficient to convey romantic love. And perhaps that’s how it should be. Love is, after all, a deeply personal, subjective, and, yes, often selfish emotion. I just know that I can read all the romantic poetry and novels, watch all the romantic movies, and listen to country music 24/7, but I’ve come to know and understand that I’ll never be able to adequately convey the depth of emotion I felt that night in Santiago.

But the overt racists, the Klan and other white supremacists, had been more or less relegated to the shadows. When Obama was elected President of the United States, I, like so many others cried with joy. I felt an overwhelming sense of optimism and hope for the future of our country. I was sure the pre-election racists with their birther conspiracies, the internet memes likening Obama to a monkey, and other idiocies, would once again retreat to the dark corners of our society—hateful cockroaches scurrying away in defeat.

That didn’t happen. Social media and propagandist television and radio programs not only kept the ugliness alive, they propagated even uglier, more crazy, more racist conspiracy theories and lies. Still, there was hope. The Obama presidency was dignified and thoughtful. It slowly and effectively pulled us out of a great recession. It calmed the terror of a nuclear Iran. It reasoned there was no way to effectively eliminate North Korea’s nukes without withstanding unacceptable human loss. It faced up to the planetary and national security threat of climate change. And, yes, the administration made mistakes as well—how do you not make mistakes in the boiling cauldron of the Middle East?

So what happened? How did a black president with high approval ratings give way to a president who was an admitted adulterer; a man who’d been sued and fined for racial discrimination; a man who defrauded investors in his business dealings to the point where no United States banks would even deal with him; a deal maker who made so many bad deals he left behind squadrons of betrayed investors; a man who thought nothing of creating a fraudulent university built on lies and flim flam; a man who called black people “lazy” and Mexicans “rapists” and said Haitians have AIDS and labelled entire blocks of countries as “shitholes.” This list of cruelties, both petty and huge, is seemingly endless. The scope of pandering to white supremacists, to the point of being endorsed by the KKK, is bewildering and frightful.

Yet the base is still there. The man who can barely articulate a comprehensible sentence when he is not doing his best to read what was written for him wields a strange power over many people who had always stood for the kind of morals Donald Trump flaunts and denigrates. One argument is that these people see an opportunity to use Trump to get their long-sought ideological goals accomplished. Deregulate employment standards. Deregulate checks against pollution. Deregulate the banks (again). Etcetera. We can put up with Trump and his disgusting sense of morality if we can get finally get what we want.

Maybe that’s it. But I think there’s a much more insidious motive behind these people’s ignominious decisions to park their morals in a long-term storage locker. After all, any far right conservative president with a conservative majority in Congress should be able to accomplish all of the above and more. I think that the real underlying fear among the Trump base is the browning of America. That age-old fear of being in the minority with the possible accompanying loss of power.

Human history is replete with examples of people gaining power based on fear. Fear of race, ethnicity, tribal affiliation, and religion. White people, black people, and Asian people have committed, and are committing, genocide based on little more than fomented hatred as a means toward power.

America may be one of the greatest melting pots in the history of the world, yet until Obama’s election, and even, arguably, despite his election, it has been ruled by the predominant racial class: whites. Things will change. Climate change will become the greatest driving force behind emigration and immigration in the near future. It will probably cause wars and certainly political upheaval. America will brown—it is an inevitability we can either embrace or fear. To embrace it, we would need to learn about and learn to respect those who may become our new neighbors. Nothing promotes fear like ignorance. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “Nothing in the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.”

Let’s not fear the changing demographics. Let’s embrace it. Let’s reject the politics of fear and hate based on racial and cultural prejudice. Let’s show the world why we have a national holiday celebrating the words and works of Martin Luther King, Jr.

As Ghandi said: “The enemy is fear. We think it is hate; but, it is fear.”

My conclusion is that there are two separate and distinct issues at play. Can facts themselves be subject to varying interpretations? Perhaps. As a former personal injury attorney I would often be in agreement with the insurance defense attorney as to the facts how an accident happened (Party A’s car T-boned Party B’s car in an intersection, for example), but we would have diametrically opposed positions on the precipitating events which led to the accident (causation).

There are, however, some facts which I have an extremely difficult time conceding to be open to interpretation. Climate change is a prime example. It is a fact that close to 100% of climate scientists believe in climate change caused in part by humans. Most people refer to the percentage as 97%, but the fact of the matter is that there have been no scientific peer-reviewed papers published in years which take the contrary view. As astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson, said, if anyone thinks the scientific view of climate change is some kind of hoax, they don’t know a thing about science. Scientists love to tear each other apart. They tend not to agree on anything until the science is deemed proven.

So how can so many lay people simply reject the scientific consensus on climate change? How does someone with no scientific background and no actual knowledge or understanding of the scientific data, decide that he or she is more intelligent and more knowledgeable than scientists (including NASA scientists) who have spent their lives studying the issue? Is that some special level of intellectual arrogance? Or is it merely a refusal to actually process the information on a critical thinking level and instead accept the non-scientific tribal/political stance taken by so many anti-government politicians and pundits?

Do people who deny the science of climate change claim to have applied critical thinking to the established science and came to the conclusion that all the scientists were wrong? This is where the dichotomy of processing information is at play. I suspect that there are a number of people who believe they have done their due diligence by reading certain articles which support their initial inclination that humans are not affecting the climate and that whatever changes we are experiencing are simply part of the natural occurring process. But I also suspect that a larger group of people make no effort to analyze the facts themselves, but instead rely on their favored pundits to tell them how to think.

Let’s take the non-critical thinkers out of the discussion for now. Those who make no attempt to put some effort into actually thinking about what certain facts mean and instead rely on their favored source of propaganda to form an opinion are nothing more than lemmings. This, by the way, is true on all sides of the political spectrum. Reposting Facebook or Twitter posts without making any attempt to establish the veracity of the post is nothing short of lemmingesque. I recently ‘unsubscribed’ to a progressive, Democratic site after determining that too many of its postings were not properly vetted or were over-the-top hyperbole.

We’re then left with the basic question over which I often obsess: when two people are presented with the exact, undisputable, set of facts, what is it that allows them to adamantly formulate completely disparate opinions? Are facts obsolete as facts? Are facts now little more than sociological tools to be manipulated or ignored in favor of a desired outcome?

Of course, when considering this issue, Donald Trump comes to mind. It is well established that the man is a prodigious liar and that he has made so many outrageous and offensive statements that it is becoming a daunting task to document. But one thing he said during the campaign stands out to me as a prime example of how divergent people can be in the processing of a fact. In the infamous Billy Bush incident the Trump quote that generated the most attention was the pussy grabbing quote. It was crude and ugly and newsworthy and in campaigns past would have immediately disqualified the candidate from continuing on in the race. Yet Trump supporters and even his wife shrugged the statement off as “locker room talk.” Okay, I’ve heard (and said) a lot of crude things in locker rooms over the years, although never quite on that level, but I’ll play along with the fantasy that such a statement about assaulting women was just boys being boys.

But what shocked me most about that whole scenario wasn’t the pussy grabbing bravado, it was the statement that Trump had tried to fuck another celebrity after “going after her like a bitch” (whatever that means). In other words, Trump admitted to attempting to have sex with another woman while his wife, Melania, was pregnant! Think about that. That isn’t locker room talk—that’s a recital of events (and quite believable given that he was a known adulterer).

So how did Trump supporters, many of whom are evangelical Christians, and most of whom over the years have tried to claim the mantle of being in the party of family values, process that statement? That the statement was made and recorded is an absolute fact. Yet its content and meaning was processed and interpreted in varying ways. To me, it showed the character of a despicable human being, willing to flaunt his crude attempts at infidelity to a wife carrying his child. Yet to others it was covered by the claim of “locker room talk” or otherwise simply dismissed as not important. What was it that allowed a person who should have been disgusted by Trump’s admission to rationalize it away and instead wanted the man to be the President of the United States?

I guess we come back to the tribal politics which all too often expose our willingness to be hypocrites if it advances our particular ways of thinking. I say “I guess” because frankly I don’t know, and that’s what makes the issue so obsessive with me. It’s a never-ending source of fascination to me how people can vote against their own interests; be Christian yet accept non-Christian-like insults and actions; shrug off an impressively huge compendium of lies; and think themselves smarter than NASA scientists.

It would, of course, be the height of hubris for me to say or imply that everyone should think like me. That would be boring, unproductive, and uncreative. I love the fact that one person’s interpretation of the fact of a flower is a smattering of paint thrown toward a canvas. It’s just that I begin to get a wee bit concerned when interpretations of facts such as climate change threaten the very existence of life on our planet.

David Myles Robinson

As will become readily apparent, my blogs will not just be about my books or even writing in general. They will be about whatever suits my fancy--and yes, I'm sorry, but that may include politics from time to time. We live in an interestingly tempestuous time and as a writer I find it impossible to ignore the worldwide psycho-drama (and, at times, psycho-comedy) being played out before us on a virtual daily basis.

Archives

May 2021

January 2021

June 2020

February 2019

July 2018

May 2018

March 2018

January 2018

October 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

Categories

All

Africa

America

Appreciation

Author

Chimps

Climate Change

Cuba

Data

Diversity

Eyhnicity

Facts

First Book

First Novel

Friendship

Golf

Hate

Historical Fiction

Humiliation

Illness

Immigrants

Incivility

Inclusivity

Kennedy Assination

Legal Novels

Legal Thrillers

Love

Maggots

Martin Luther King Jr.

Movies

New Mexico

Obama

Political Debate

Politics

Quest For Truth

Race

Racism

Religion

Risk

Romance

Rwanda

Santiago

Science

Sell Out

Serengeti

Summertime

Taos

The Big Fail

The Pinochet Plot

Travel

Travel Illness

Triumph Of Sprit

Tropical Series

Trump

Understanding

Witer

Writing

RSS Feed

RSS Feed